An ever-expanding network of papers and ideas (in theory).

Keeping up with scientific literature seems like an impossible task. Countless papers are published each month, and there are numerous older papers worth reading. The to-read-folder on your computer continues to grow, sucking in more and more unread papers. A black hole feeding on PDFs. If this sounds familiar, I might have a solution for you: building your very own literature network.

A Second Brain

The idea for a literature network came to me after watching some YouTube-videos by Tiago Forte. He has recently published a book, entitled “Building a Second Brain“. I have not read the book yet, but the main concept – which is nicely covered in the videos – is relatively straightforward. Designing a virtual system to collect and store relevant information. I will not go into the details of the entire system here. The relevant idea for this blog post is C.O.D.E. which stands for capture, organize, distill and express.

- Capture = Keep what matters and resonates

- Organize = Save for future action

- Distill = Boil down and find the essence

- Express = Show and share your work

This process can also be applied to scientific literature. As you explore the vast ocean of published papers – using your favorite search engine of ResearchRabbit – you come across many interesting studies. The first step is to capture the relevant papers and add them to you literature network (I will explain how later on). An important aspect of this capturing step is that you should “keep what matters and resonates”. Which brings me to another concept: Zettelkasten.

Making connections

A Zettelkasten (German for “slip box”) consists of small items of information stored on paper slips or cards that may be linked to each other. This system is often attributed to the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann who created a Zettelkasten with more than 90,000 index cards, enabling him to write prolifically. I came across this concept when reading the book “How to Take Smart Notes” by Sönke Ahrens.

The main take-away from this system is to make connections between index cards. And the same applies to scientific papers. Research is not done in a vacuum (unless you are a physicist). Scientists build upon the work of others. Whenever you come across an interesting paper, you should ask yourself: How can I relate this to other papers or concepts that I already know? That is the second step of the C.O.D.E. approach: organize your scientific literature.

As you continue to collect and connect different papers, you can start to distill important ideas from them. One important aspect of the Zettelkasten-system is that new connections will emerge unexpectedly. You might bring together two seemingly unrelated ideas, culminating in an ecstatic aha-moment. Once you have gathered enough ideas, it is time to express them. Write the first draft of your paper, using the information in your literature network.

Introducing My System

In theory, this system sounds amazing. But it has been a struggle to put it into practice. After many failed attempts, I might have found a way that works for me. Let me walk you through it.

First, you need software to capture your scientific papers. I have experimented with Notion, but that did not work for me (although I still use it for other things). Eventually, I settled on Obsidian. This software is freely available, can be used offline and allows you to visualize your network of notes. Whenever I come across a relevant paper, I save it as a note in Obsidian. This note has the following sections:

- Title of the paper

- Author (year) Journal

- Abstract with highlights

- Why it is relevant

- Connections with other papers

- Notes and Quotes (added once I read the paper)

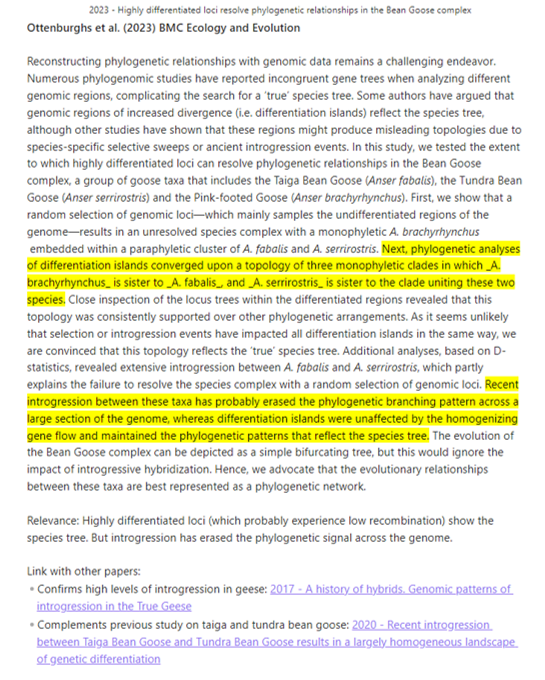

Here is an example note from one of my own papers.

To Tag or not to Tag

Apart from paper-notes, I also have notes related to projects (e.g., manuscripts that I am working on) and ideas. These project-notes and idea-notes are connected to numerous relevant papers. Over time, I hope that interesting connections will emerge. For a while, I tried to accomplish this by using tags and keywords. But the proliferation of new tags became so messy that I abandoned that idea (although it might work for you).

At the moment, I use a color-scheme in my network with my own papers in green, project-notes in blue and idea-notes in red. Papers that I have covered on my Avian Hybrids blog are highlighted in yellow. My network is not that expansive yet, but it already looks nice.

I have no idea how my literature network will develop in the future. And it could well be a waste of time. But currently, I am having a lot of fun with it. Adding paper-notes and making connections is very addictive. And I feel that my thinking has become more clear. Who knows what brilliant ideas will emerge from my network…